Big data conveniences invade users’ privacy by taking their personal information. Then they threaten the users’ with an identity prison: in small ways and large, we are lured and coerced to actually be the person defined by our accumulated big data profile.

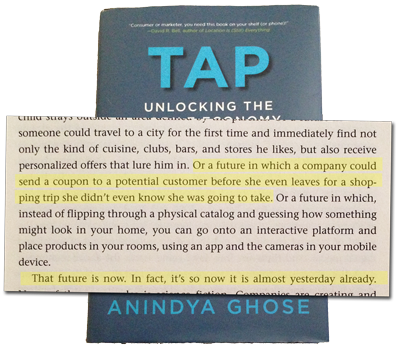

In his book Tap, author Anindya Ghose sees a future in which a company could send a coupon to a potential customer before she even leaves for a shopping trip she didn’t even know she was going to take.

If this is the future, if what we want to buy, and where we decide to go, and when we choose to depart, if all that is all stimulated for us, and to accord with habits and desires already established and organized on remote databases, then there will never be anything more to know: we won’t ever be anyone but the person replaying the role we’ve already been.

There are three responses.

One is surrender. In 1999, Sun Microsystems CEO Scott McNealy notoriously asserted, “You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”

The second is reclusive: protect privacy and control over identity by avoiding the conveniences of the data gatherers. If you don’t buy from Amazon, refuse to hail an Uber, never consult WebMD, travel without Airbnb, and fail to set up a Facebook account, the algorithms won’t churn out reliable profiles of your tastes, habits, debilities, travels and relationships. For internet surfing, it’s best to use a virtual private network, or TOR. For cell phone service, a burner will do. When brick-and-mortar purchasing, use cash. In general, the guiding verb is to hide: do what’s necessary to shield your private information.

The third response to big data’s privacy threat is dynamic: accept big data conveniences, but also create new conceptions of intimacy and individuality that are equipped to subsist within the transparent environment of algorithmic capitalism. The idea here is to rethink what privacy means, and also how we generate conceptions of ourselves, so that we can retain control over our information and autonomy, even while submitting (at least partially) to the invasion of the data platforms.

A rhizome is a plant stem with a particular characteristic: when it’s severed, each segment continues growing independently. Moving the idea over to human identity, the idea is that it’s a natural part of existence, not an unnatural aberration, to at least periodically break clean away from the person we have been, and grow in a different direction. Dissociation from our own past means fundamentally reforming our tastes, aspirations, desires; what drives us changes. And if the changes run deep enough, then the information the data platforms have accumulated to describe, predict, and lure us is deactivated: the data no longer describes the person we’ve become.

Living as a rhizome means protecting your privacy and controlling your own identity not by hiding your personal information, but by escaping it. Instead of concealing where you’ve been and protecting details about what you enjoy and despise, you cut away and into someone else.

This strategy of recovering privacy and identity by changing who we are isn’t for the faint-hearted, but it’s not prohibitively perilous or fantastically rare either. It happens every summer that young people depart for a backpacking travel somewhere in the world and soon discover that they can more or less create themselves as whoever they wish for the strangers they meet. Of course, the fact that no one is running background checks on their fellow night-train travelers doesn’t automatically convert everyone into vivid explorers of experiences they wouldn’t engage were their friends or parents watching, but, every time a generation goes abroad, there’re always a few who go native, or meet someone and go somewhere else where they may live a different language, or distinct kind of life. Whatever the particulars, they never go back: not to where they’re from, not to who they were. A maximum example would be the late 19th century voyager Isabelle Eberhardt, but if you visit the travel section of your local bookstore, you’ll find volumes of narratives written by people you’ve never heard of, all telling the same story about becoming someone else abroad.

Traveling somewhere else and going native doesn’t happen to everyone, but anyone who steps back and observes will begin noticing semi-radical versions of that transformation all around. There’s the Wall Street shark who gives up the suits and Adderall and starts a surf camp, the journalist who trades an electric and connected life for an ice cream stand in a country she’s never visited. There’s the criminal who becomes a cop, and the other criminal who becomes a heroin addict. The football player converts into a priest, the lady’s man comes out of the closet, the reckless and free daughter has her own child. Every time one of these metamorphoses occurs, there’s an escape from big data oppression: the collected information – the past – no longer applies.

The term rhizome as applied to a lifestyle traces back to the late 20th century philosopher Gilles Deleuze. Other scholarly connections lead through psychological studies of dissociative identity. Regardless, there are two theoretical keys to the kinds of transformations that lead escapes from the big data identity prison.

The idea of privacy as something created instead of preserved or hidden, means that our defining personal traits, numbers, orientations, and impulses are not dragging along behind us, instead, they’re generated. Religious belief, for example, is a critical and personal element of a data profile, and every time someone converts to a new faith, they’re constructing privacy information. That’s what the French writer Isabelle Eberhardt did when she converted to Islam. More contemporaneously (and polemically), there’s the case of Yvonne Ridley who also produced her own privacy on the level of faith.

Or, when a Wall Street banker checks out and heads to the Caribbean to teach surfing, that’s not only a change in the weather but a switch in basic values. The question about what’s worth having and what’s worth doing with the only life we’ll ever have is coming back with different answers.

Or, on the most tangible level of privacy, there’s biological information. Some cannot be escaped (genetic traits, future vulnerabilities related to past injuries), but other aspects may be produced. There are the psychological and physical conversions that come with exercise and diet changes, or with drugs and surgery. Even tattoos, piercings, and similar body modifications may reformulate the delicate and intimate elements defining who we are.

Finally, whether the area of personal information corresponds with faith, aspirations, or physical conditions, privacy endures by producing personal information. Secrets are no longer kept, they’re rendered invalid.

There are two ways to understand where my identity – who I am – comes from in time. One starts from the past, the other begins in the future. The difference can be conceived grammatically, in terms of nouns and verbs.

When my identity traces to the past, we say that there is someone who I am, and then because of that, I do what I do. For example, I may be a person who regularly emails friends in Mexico. Because that network is part of who I am (the noun), you can expect that what I do (the verbs) will follow along afterward. It shouldn’t be surprising, consequently, to find that I’m the kind of person who’d be particularly tempted by the opportunity to visit the country. What’s certain is that big data platforms work on this logic: they find out who you are by scanning your emails, and then use the gathered data to predict – and profit from – what you might subsequently do. This is the Google business model. It’s also why I constantly get served online ads for Cancún airfares and hotel deals.

Identity can also be conceived the other way, however. I do what I do, and the person I am comes after, as an effect of what has been done. In other words, to know who I am, you first need to see my behavior. If that’s the order – if it’s the verb of what is done before the noun of who I am – then the full definition of what it means to be me is always just over the horizon: we’re always waiting for it to come after witnessing the latest act.

Examples are common. For instance, we say that we fall in love because we don’t know beforehand who we're going to find enchanting. It’s only because I’m falling for someone, that I become the person who loves. The verb comes before the noun; you love before you are identified as the one who loves.

Or again, no one drinks to excess because they're an alcoholic; they become an alcoholic because they’ve been drinking, excessively.

Across experience the logic repeats. Many young adults have little sense of the career they’d like for themselves. For some the uncertainty never ends, but others happen into a profession and acquire the taste. Maybe a woman studies theoretical mathematics in college, but finds the work too abstract until stumbling into a job at Tableau where number avalanches get applied visually: by doing it, she learns that she’s a mathematical engineer.

Or, maybe someone who starts out playing on the college soccer team acquires a taste for the regimens of training and diet, and so becomes a trainer or dietitian. Or, there’s the aspiring actress who works part time as a waitress before becoming a fulltime waitress, before taking the leap, buying her own boutique establishment, and so becomes a restaurateur. The paths are infinite, but every one is the same in this way: what you do becomes who you are. The verbs come before the nouns and the I – as in who I am – is always just out of reach in the future because we won’t know for sure exactly what it is until we’ve already stopped doing things, which is a fatal condition.

Big data relates to privacy and identity in two ways. One is oppressive, the other enabling.

Big data platforms oppress when they claw for private information and exploit it to confine users. Your identity becomes inescapable when every romantic partner you meet, every film you see, and every trip you take is filtered and proffered to correspond with a data profile accumulated from your own past and stored underneath a cooling tower thousands of miles away. Every new person and experience resembles the last one. In the end, this is the deepest ethical risk of big data reality: collapsing privacy leading to withered individuality.

But there’s another side to the same technology and facility. Just as it's true that it has never been easier to get trapped in a single identity, so too it has never been easier to get out of who we are, to disrupt our existences from the bottom up by connecting with unfamiliar aspirations, tastes, desires, and directions. Travel has never been easier, and the information flows that trap us all in our customs and habits also provide narrow windows onto completely unexpected experiences. Just taking the simplest example of shared realties that is YouTube, it’s undeniable that you need to reel through a punishing number of cat videos to find something interesting, but despite that there are curious destinies out there. Or, take LinkedIn: only a generation ago the job search was more or less limited to the advertisements found in the local newspaper, and the doors that could be knocked-on around town. Now, accessible openings feed to our screens on an international scale, and for those who make a resonant appeal to the recruiter who’s willing to take a chance, they can be gone the next day.

The two resisting responses to big data’s privacy invasion imply distinct ethical tasks.

If hiding is the strategy, then the central ethical task is to help people protect their information. This leads to the incipient movement in privacy by design. The idea here is that big data platforms initiate projects with data protection prioritized: from the first page of the designing and programming, steps will be taken to ensure that users’ information remains secure, instead of escaping into the hands of freewheeling databrokers. It’s difficult to object to these kinds of public interest initiatives, but it’s even harder not to recognize that the money is on the data gathering side, which means the wildcatters prying the data out are going to be getting better rewards than the technicians assigned to keep it safe. The consequences of the imbalance are not difficult to foresee.

If escape is the strategy, then the ethical task assigned by big data reality isn’t to design privacy in, it's to design monotony out; it is to ensure that everyone is tempted not by the sure thing, but by the unexpected, the idiosyncratic, the weird. At least initially, the economics don’t line up well for this strategy, either. After investing rivers of money in the attempt to identify exactly who their users are, it’s difficult to imagine why data platforms would then respond by feeding back content (romantic partners on Tinder, product suggestions on Amazon, career opportunities on LinkedIn) that’s not suited to the recipient.

It is standard practice on some platforms to intentionally introduce anomalies from time to time, to test how users respond to possibilities that they wouldn’t otherwise be served. So Tinder may present a man who loves jazz to the woman whose ears still ring from last night’s metal concert. But, even here, the reason for including incongruent experiences is not to provide opportunities for the users to escape their profile, it is to refine the ability to define the users still further, to hold them still tighter, and to predict matches still more accurately.